Private Equity, a Blessing or a Curse?Case Study on Classic PE Deal: 3G Capital’s Acquisition of Burger King

Now that we are almost halfway through the year, it is apparent that at least the first few months of 2025 have not manifested the M&A boom that many were expecting just several months ago. M&A talk has been overshadowed by tariff talk and it seems almost impossible to go through a day without hearing a mention of new policy developments from Trump on Truth Social. So today, instead of adding to the endless abyss of macroeconomic and trade policy speculation, why don’t we revisit a much merrier time when interest rates were lower, iPhones still required “slide to open,” and Messi vs Ronaldo was still a novel debate— The 2010s.

In the late summer of 2010, Burger King was not in a happy place. The burger giant, home of the iconic Whopper, had lost significant ground to rivals like McDonald's and Wendy's. Sales were sluggish, innovation was lacking, and Wall Street had largely turned its attention elsewhere, viewing Burger King as a stagnant brand in desperate need of rejuvenation. Shares hovered around $16, stuck in neutral, reflecting investors' waning confidence in the company's ability to drive sustainable growth.

But perhaps it was exactly because of the increasingly pitiful performance of Burger King that 3G Capital— a Brazilian American private equity group— saw a glimpse of opportunity to take private the ailing King and help lift it back on its throne. On September 2, 2010, 3G Capital made headlines by proposing to acquire Burger King for $24 per share—a 46% premium to its previous day's trading price. The offer valued Burger King at approximately $4 billion, with around 70% debt financing, creating what was a classic leveraged buyout structure designed to use debt to amplify returns, but also carried significant risk given the size and scale of the operation.

Initially, the markets reacted positively, sending Burger King's shares soaring close to the deal price within hours. Observers noted the audacity of 3G’s bet: Burger King, at that moment, was the second-largest burger chain globally, a position commanding respect yet burdened by weak margins, operational inefficiencies, and a sprawling, bureaucratic corporate structure. The industry context was equally unforgiving, with intense competition from fast-casual entrants and rapidly evolving consumer preferences. Few doubted that substantial surgery would be needed. The critical question was whether 3G's famously austere management style and penchant for radical cost-cutting could resuscitate or further imperil the iconic flame-griller.

Yet, from 3G's perspective, the calculus was clear. The buyout firm’s partners, Brazilian billionaire Jorge Paulo Lemann and his colleagues Marcel Telles, Carlos Alberto Sicupira, and Alex Behring, are veterans of aggressive turnaround projects at global brands like AB InBev and later Kraft Heinz. Their trademark approach, revolving around disciplined cost management and asset-light business models, was not new, but it was still undeniably bold. In Burger King, they saw a beloved but neglected brand sitting atop an under-exploited global footprint and weighed down by unnecessary corporate overhead.

The acquisition closed rapidly on October 19, 2010, following swift approval from Burger King's board. The transaction was supported by financial advisory heavyweights, with Lazard, J.P. Morgan Securities, and Barclays Capital arranging financing for 3G, while Burger King relied on Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs as advisors. On the legal front, top-tier firms Kirkland & Ellis represented 3G Capital, and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom counseled Burger King. Such a lineup signaled clearly that 3G's acquisition was both structurally sophisticated and carefully executed.

Source: Forbes

From the outset, 3G Capital’s strategy with Burger King has often been characterized as a classic turnaround play: “slash, scale, reinvest.” And on the surface, the sequence holds. Burger King did cut costs aggressively, franchise stores, and eventually reinvested in brand and operations.

But that framing, to me, misses the deeper logic of the playbook—a perhaps more unappealing logic that looks far more like:

Slash and Optimize → Merge → Slash Again.

What began as a cost-efficiency push evolved into a platform strategy. First, 3G slashed corporate overhead through zero-based budgeting and a cultural reset. The headcount at Burger King's Miami headquarters dropped from around 800 to fewer than 300. Executive perks were eliminated, every line item required justification from scratch, and EBITDA margins soared. Next, 3G refranchised more than 1,300 company-owned stores, flipping Burger King into an asset-light royalty model. Cash flow smoothed out, capex demands disappeared, and the business shifted from operating restaurants to collecting fees. With margins expanding and leverage ticking down, 3G saw Burger King as a financial platform in waiting for a merger.

That platform emerged in 2014 when Burger King acquired Tim Hortons in an $11 billion deal that formed Restaurant Brands International (RBI). Over time, RBI would also go on to absorb Popeyes and Firehouse Subs, the pattern was clear: acquire, optimize, layer on, and repeat. The pattern is so clear even without looking at 3G’s other famous deals like AB InBev and Kraft Heinz (We’ll touch upon those later).

Within three years of the original buyout, Burger King’s EBITDA had surged by 32%, its leverage fell into the low-20% range of enterprise value, and equity valuation multiplied several-fold. But reinvestment—at least in the traditional sense of customer-facing innovation—wasn’t central to that early success. “Reclaim the Flame,” the long-awaited store and brand revitalization effort, wouldn’t come until 2022—over a decade later. What 3G engineered was less of a brand revival and more of a structural transformation by turning a bloated U.S. operator into an asset-light, scalable, and cash-yielding platform. But although this playbook had worked out well for 3G and Burger King, the aggressive cost-cutting and operational frugality don’t always work out for private equity.

In fact, what fascinates me the most while diving into the rabbit hole of private equity investments in restaurant franchises is that private equity’s impact on restaurant chains is far from uniformly positive, and 3G’s triumphant Burger King turnaround stands in stark contrast to several high-profile private equity-backed disasters. For instance, 3G’s buyout of Heinz, and the later operations of Kraft-Heinz are not something that 3G is necessarily proud of on their track record. Furthermore, other private equity-owned businesses like Red Lobster, faced Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2024, dragged down by an ill-advised real estate sale-leaseback arrangement under Golden Gate Capital’s ownership that saddled the chain with escalating rental obligations. Similarly, Quiznos saw its franchise network decimated after PE ownership drove franchisees away through aggressive fees and underinvestment, shrinking the chain from over 5,000 to fewer than 400 locations.

These cautionary tales pose a critical question that lies at the heart of this analysis: Under what conditions is private equity capital a “blessing,” and when does it turn into a “curse” for consumer-facing brands? Using Burger King as Exhibit A, this blog aims to dissect precisely how and why 3G’s playbook unlocked substantial value, while simultaneously shedding light on the pitfalls that can doom similar strategies in less capable hands.

In the following sections, we’ll explore how Burger King transformed from a bloated legacy fast-food brand to an agile, asset-light powerhouse. We’ll also dig deep into why Wall Street is enamored with royalty-driven business models and why more and more PE shops are looking to acquire/already acquiring franchises (i.e. Roark acquiring Subway, Blackstone acquiring Jersey Mikes). We’ll also examine the financial mechanics of this classic LBO, consider the broader implications for private equity as both a blessing and curse, and carefully weigh the bull-and-bear case for 3G’s future. Finally, we'll also distill actionable lessons for aspiring investors/entrepreneurs and preview 3G’s bold next act: its $9.4 billion move to acquire Skechers.

Company Overview:

The first Insta-Burger King in Jacksonville, Florida. Source: Burgerbeast.com

Burger King

Long before flame-grilled Whoppers and billion-dollar buyouts, the Burger King story began in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1953, not as a fast-food juggernaut, but as a struggling upstart called Insta-Burger King. Its founders, Keith Kramer and Matthew Burns, were inspired by a pilgrimage to Southern California, where they had seen the streamlined efficiency of the original McDonald’s. Determined to replicate the “Speedee Service System,” they returned home and licensed a set of machines called the “Insta” devices: one rapidly produced milkshakes, and the other, the Insta-Broiler, was designed to cook burgers en masse through a conveyor-fed heating system. But the machinery failed them, and the Insta-Broiler routinely malfunctioned: overheating, unevenly cooking patties, and producing inconsistent product quality. Customer complaints mounted, franchisees began to bleed cash, and operations stalled. The original model, built on scale-through technology, was on the verge of collapse. What should have been an engineering marvel quickly turned into a cautionary tale.

Yet over 300 miles south in Miami, two men saw an opportunity in the rubble. Cornell hospitality grad James McLamore and business partner David Edgerton opened their own Insta-Burger King franchise in 1954 and immediately confronted the same technical flaws. But rather than fold, they innovated. Edgerton went to work in his garage and invented the Flame Broiler—a gas-powered, open-flame conveyor system that not only solved the functional breakdowns but created a new selling point: flame-grilled flavor. And that same flame-broiled flavor is still Burger King’s hallmark today. Armed with this breakthrough, McLamore and Edgerton moved fast. In 1957, they launched the Whopper—a 37-cent behemoth designed to compete on both size and perceived quality against McDonald’s smaller hamburgers. The name itself was chosen for impact: “Whopper” suggested abundance, indulgence, and premium status. It worked. Customers loved it. The Whopper became the company’s anchor product, and its success allowed the brand to shake off its faltering past. The duo also made the strategic decision to drop the “Insta” prefix, rebranding the company simply as “Burger King”—a move that symbolically marked a break from the tech-reliant failures of its origin.

In the years that followed, the company expanded across Florida, and by 1959, there were more than 40 locations. Eventually, McLamore and Edgerton bought out Kramer and Burns, and despite Kramer and Burns being the original founders of Burger King, it was without a doubt that McLamore and Edgerton were pretty much doing all of the heavy lifting of building out the franchise. From there, the two new owners began shaping a vertically integrated enterprise. McLamore and Edgerton founded Distron, a distribution company, and Davmor Industries, which manufactured proprietary kitchen equipment. These internal capabilities provided early versions of supply chain control and standardization—critical enablers for franchising at scale.

After a few years of increasingly rapid growth, Burger King’s first major inflection point came in 1967 when it was acquired by Pillsbury. The food conglomerate, eager to expand beyond baking, gave Burger King the financial backing it needed to challenge McDonald’s on a national level. During the 1970s, the brand began formalizing marketing efforts, expanding its menu, and increasing its footprint across the U.S. and abroad. The Whopper became iconic, and taglines like “Have It Your Way” and “Home of the Whopper” etched themselves into consumer memory. However, becoming a part of a much bigger conglomerate, Burger King was never quite able to maintain operational consistency. It lacked a centralized, founder-led culture like McDonald’s had under Ray Kroc. Management turnover became frequent after both McLamore and Edgerton left the franchise since their individual visions began to diverge too much from what Pillsbury had planned for the Burger King brand. Finally, after Pillsbury was acquired by Grand Metropolitan in 1989, Burger King became a mere pawn in a series of corporate chess games. It passed through Grand Met’s merger with Guinness to form Diageo in 1997, and then to a consortium of private equity firms—TPG Capital, Bain Capital, and Goldman Sachs—in 2002. Each transition brought new strategic mandates, many of which conflicted or overlapped: speed of unit growth, branding overhauls, international expansion, and technological upgrades. But execution faltered. By the early 2000s, Burger King was struggling to find its voice. Its most famous ad campaigns—like the bizarre “Subservient Chicken” or the creepy “King” mascot—went viral, but sales didn’t follow. The “Have It Your Way” brand message clashed with real customer experiences, and franchisee relationships in the U.S. began to fray. Between 2002 and 2010, Burger King cycled through more than six CEOs and multiple turnaround attempts. Meanwhile, McDonald’s, armed with the power of its Dollar Menu and a more focused global strategy, widened the gap.

Pillsbury acquired Burger King in 1967.

Yet despite its operational setbacks, Burger King retained a powerful set of structural assets: a globally recognized brand, a strong core product (the Whopper), a legacy of flame grilling, and a franchised footprint that limited capital expenditure. At its peak before the 3G acquisition, Burger King had around 12,000 locations globally, and a presence in over 80 countries. But it wasn’t growing. Same-store sales were sluggish, capital expenditures remained high, and lawsuits with franchisees over pricing strategy (notably the controversial $1 Double Cheeseburger) revealed deep internal misalignments. That’s when 3G Capital saw an opening. In 2010, the Brazilian American investment firm acquired Burger King for $4 billion, paying a 46% premium to its stock price at the time. But what 3G brought wasn’t just capital—it was a new cultural operating system. Alex Behring, Daniel Schwartz, and the 3G team implemented their now-famous playbook: zero-based budgeting, lean corporate structures, and aggressive performance metrics. The company slashed corporate overhead, flattened management layers, and relocated its headquarters to Miami. Within months, Burger King’s capital expenditures dropped, and its free cash flow surged. Perhaps most consequentially, 3G pursued a strategic pivot to a 100% franchised model, a move that dramatically reduced Burger King’s capital intensity and shifted risk to operators. The unit-level economics improved, and the company regained financial flexibility. Then came the growth push. Using a hub-and-spoke model, Burger King partnered with master franchisees in emerging markets—first Brazil, then China, India, and France—to accelerate global store openings. In France, where Burger King had virtually no presence at the time, the brand rebuilt from scratch and eventually became one of the country’s leading QSR chains.

Burger King in China. Source: Eataku

But 3G wasn’t done. In 2014, it merged Burger King with Tim Hortons in a $12.5 billion deal, forming Restaurant Brands International (NYSE: QSR). That vehicle would later absorb Popeyes in 2017 and Firehouse Subs in 2021. RBI retained Burger King’s asset-light franchise model but layered in shared services, digital transformation initiatives, and global marketing scale. Burger King’s product line, operations, and customer experience have since been refined under RBI’s data-driven approach. By 2024, Burger King had grown to over 19,000 stores globally and contributed to RBI’s $50+ billion enterprise value. Yet the brand remains in active transformation. It has launched its “Reclaim the Flame” campaign to reemphasize the Whopper and modernize U.S. operations. It has invested in digital kiosks, delivery infrastructure, and revamped menu boards. Internationally, growth remains robust, especially in Asia, where population density and QSR penetration trends continue to favor Burger King’s master franchise model.

Burger King’s evolution can almost be seen as a parable for aspiring business owners: born from imitation, nearly crushed by technical failure, saved by innovation, corporatized, fragmented, and ultimately revived through ruthless operational discipline and global scale. And yet, despite all the financial and operational engineering the brand has endured, something elemental remains unchanged: the so-called “King,” nearly 70 years after its founding, continues to chase the burger crown from McDonald’s.

3G Capital

The three founding partners of 3G. From left to right: Carlos Alberto Sicupira, Jorge Paulo Lemann, and Marcel Telles.

Founded in 2004 by Brazilian investors Jorge Paulo Lemann, Marcel Telles, and Carlos Alberto Sicupira, 3G Capital has revolutionized the private equity landscape through its distinctive "owner-operator" approach. The name "3G" derives from "three garotos" (Portuguese for "boys"), reflecting the decades-long partnership between these three billionaires whose combined wealth exceeds $40 billion. Their relationship traces back to the 1970s when Lemann—a former professional tennis player who competed at Wimbledon—founded Banco Garantia, which became Brazil's largest investment bank before being sold to Credit Suisse for $675 million in 1998.

Headquartered in New York City, 3G Capital stands apart from conventional private equity firms by deploying a focused investment strategy—concentrating its resources on a single platform investment at a time rather than managing diversified portfolios. With approximately $14 billion in assets under management (as of year-end 2023), the firm creates purpose-built investment vehicles for specific opportunities, with partners serving as principal investors, ensuring unprecedented alignment with portfolio company outcomes. Unlike traditional private equity, the majority of 3G's capital comes from its partners' personal wealth, with investment opportunities extended only to select wealthy families and investors like Warren Buffett and Bill Ackman.

At the heart of 3G's methodology is a playbook so disciplined it borders on doctrine: install trusted operators from its inner circle, implement zero-based budgeting (where every dollar must be justified from scratch), and eliminate inefficiencies with near-religious zeal. Executive compensation is heavily tied to equity, aligning incentives for the long-term value creation. Spearfishing, as co-managing partner Behring once described, isn't about catching every fish—it's about waiting for the right one, then pulling the trigger without hesitation. And what if there are no more costs to slash? As we will see throughout the firm’s history, the answer is clear: find another company to merge with, and cut costs from the newly formed, and more importantly, larger enterprise.

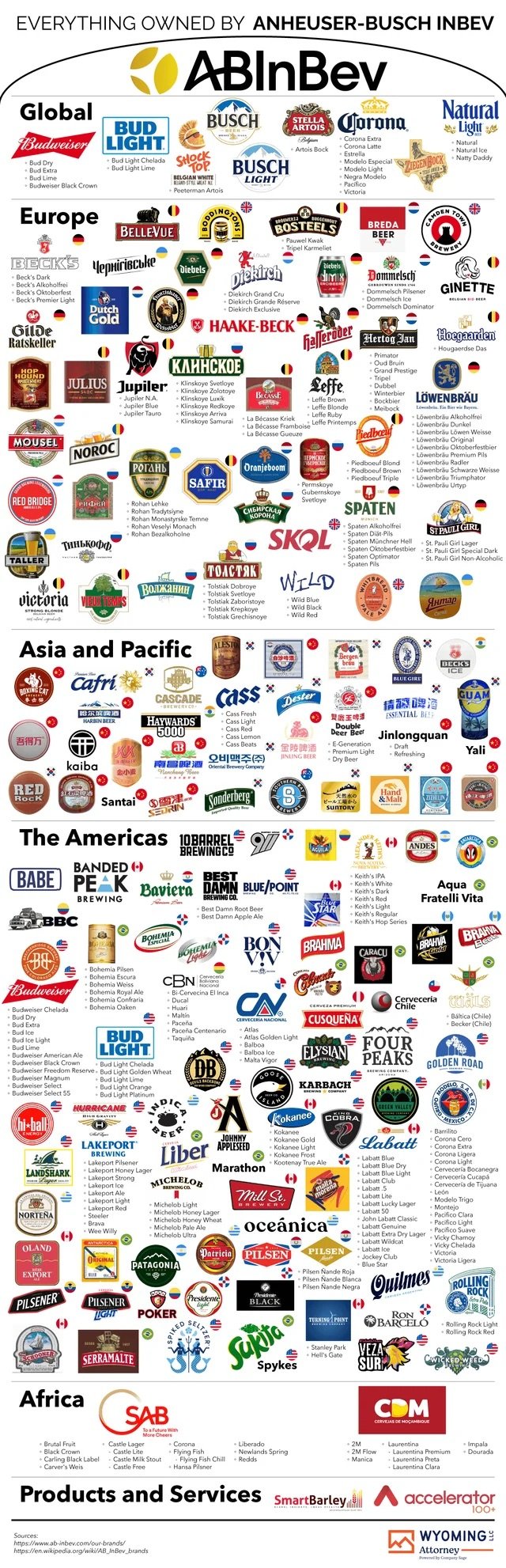

3G's investment track record begins with its brewing empire. The founders had owned stakes in Brazilian beer brands since 1989, and through a series of audacious deals, created the world's largest beer conglomerate. In 2004, they engineered the merger of Belgium's Interbrew with Brazilian AmBev to form InBev. This was followed by the landmark $52 billion acquisition of Anheuser-Busch in 2008, creating AB InBev. The consolidation continued with the $100+ billion SABMiller acquisition in 2016. Under 3G's influence, AB InBev became what industry observers called "a profit- and margin-generating machine," implementing the firm's signature zero-based budgeting and ruthless efficiency measures.

3G Capital emerged as a formidable force in the U.S. market with its landmark $4 billion acquisition of Burger King in 2010, following earlier board-level involvement in CSX and significant ownership in AB InBev. After taking Burger King private, 3G implemented its cost-cutting playbook—eliminating corporate waste, selling company-owned stores to franchisees, and even dispatching the brand's iconic "King" mascot. The firm returned Burger King to the public markets in 2012 while maintaining majority control. This acquisition became the foundation for Restaurant Brands International (RBI), a public holding company expanded through the strategic acquisitions of Tim Hortons ($11.4 billion in 2014, backed by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway), Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen ($1.8 billion in 2017), and Firehouse Subs ($1 billion in 2021).

Another significant chapter in 3G's history began on Valentine's Day 2013, when the firm partnered with Berkshire Hathaway to acquire H.J. Heinz in a $23.2 billion deal. Following its established pattern, 3G implemented aggressive cost-cutting measures, including laying off 600 workers within months. In 2015, 3G orchestrated the mega-merger between Heinz and Kraft Foods, creating The Kraft Heinz Company in a transaction valued at approximately $50 billion. The newly formed food giant quickly shed more than 5,000 jobs—over 10% of its workforce—and implemented extreme frugality measures, including directives to print on both sides of paper and eliminating free Jell-O from company headquarters.

While initially successful, with stock prices reaching $96 per share by February 2017, the Kraft Heinz investment eventually faltered. An ambitious $143 billion bid for Unilever was rejected that same month, and without another major acquisition target to implement its cost-cutting strategy, Kraft Heinz struggled to generate growth. By 2019, the company announced a $15.4 billion write-down of its Kraft and Oscar Mayer brands, revealed an SEC investigation into its accounting practices, and replaced CEO Bernardo Hees. 3G quietly exited its remaining 16.1% stake in Kraft Heinz during 2023, marking the end of a challenging chapter.

Today, as RBI's controlling shareholder, 3G Capital maintains one of the world's largest quick-service restaurant empires. In 2022, the firm acquired a controlling stake in Dutch window coverings maker Hunter Douglas for $7.1 billion, demonstrating its continued appetite for large platform investments. According to a senior partner at the firm, this investment has already appreciated significantly, with 3G turning down offers that would value their stake at "somewhere between a double and a triple, and closer to a triple." And most recently, on May 5, 2025, 3G announced it would acquire Skechers, the third-largest footwear brand globally, in a $9.4 billion take-private transaction.

Industry Overview:

Given the outrageous length of the blog, I’ve decided to have a more succinct industry overview than usual.

The franchised restaurant sector has rebounded strongly in recent years. In the United States, total food and beverage sales are projected to reach record levels of around $1.1 trillion in 2024. Quick-service restaurants (QSRs) comprise a large share of this pie – according to the 2025 QSR industry report from Mintel, the QSR market is expected to grow steadily over the next five years with a CAGR of 6.2% which values the segment at $545.2b by the end of this year.

Source: Mintel

Macroeconomic Factors Impacting the Industry:

Labor and Input Costs: Restaurants face persistent staffing challenges, with 70% reporting hard-to-fill job openings and 45% lacking sufficient staff. Despite adding 200,000 jobs in 2024, wage inflation continues. Combined with food cost increases (up 29% over four years), these factors have compressed profit margins.

Consumer Behavior: Despite economic pressures, restaurant spending has increased 13% since 2019. Many consumers find QSR formats relatively affordable compared to grocery prices, though price sensitivity has grown. Nearly half of operators plan to add promotions in 2025, while 64% of full-service patrons prioritize experience over price.

Digital Transformation: Pandemic-accelerated digital adoption has persisted, with 45% of consumers ordering takeout/delivery more frequently than pre-pandemic. In response, 73% of operators increased tech investments in 2024. Digital orders now account for over half of QSR transactions, creating both challenges and opportunities for data collection and personalized marketing.

Competitive Dynamics and Major Players:

Within the restaurant franchise arena, competition is intense between traditional fast-food (QSR) chains and fast-casual concepts. Fast-casual brands like Chipotle, Panera, and Sweetgreen, which offer higher-quality ingredients or experiential dining at slightly higher price points, captured significant market share in the 2010s. However, the high inflation of 2022–2023 tilted some advantage back to classic QSR value offerings. Customers facing tighter budgets have gravitated toward dollar menus and combo deals at burger and fried chicken chains. In response, many fast-casual players have had to emphasize value (e.g. smaller portion options or limited-time deals), blurring the line between the segments.

Another competitive dynamic is the active role of investors – particularly private equity – in the franchised restaurant space. Restaurant chains’ strong cash flows and franchising models (which are asset-light for the parent company) have attracted significant PE investment over the past decade. In fact, between 2014 and 2024, private equity firms poured over $90 billion into U.S. restaurants and bars, acquiring brands across fast food, fast casual, and casual dining. This trend has led to the emergence of multi-brand holding companies (for example, Inspire Brands owns Dunkin’, Arby’s, Sonic, and more; FAT Brands and Focus Brands have similarly scooped up numerous franchises). Such consolidation can bring efficiencies in supply chain and marketing, but it also raises the competitive stakes for independent chains. Today, many of the “major players” in franchising are PE-backed platforms or publicly traded companies with PE roots. The involvement of private equity has strategic implications (as discussed in the next section), including an emphasis on rapid growth, aggressive cost management, and sometimes high leverage – factors that can be double-edged swords for a restaurant brand’s long-term health.

Deal Rationale:

Before any models were built, one of 3G Capital’s partners conducted an informal valuation test. He asked his then-fiancée, who was a physician, and his mother, who was a lawyer, a simple question: “So McDonald’s is worth $80 billion. How much do you think Burger King is worth?” Their guesses ranged from $20 to $40 billion, which seemed reasonable given Burger King was the second-largest burger chain in the world after all. But the real number? At the time, 3G could acquire the entire business by putting up just $1 billion in equity value. In retrospect, it was exactly this gap between perception and price that formed the basis of one of private equity’s most successful consumer deals, and to dive deeper into the deal rationale behind this classic LBO, I categorized the rationale into seven key points.

First, structurally, Burger King had the foundation of an ideal private equity asset. At the time of the acquisition, more than 90% of its roughly 12,000 global restaurants were franchised, meaning the parent company earned a steady royalty on systemwide sales—typically 4% to 6%—without incurring the capital or labor costs of operating the restaurants themselves. These high-margin, capital-light income streams offered a level of cash flow stability uncommon in traditional restaurant models. 3G recognized that refranchising the remaining 1,300+ company-owned locations could dramatically simplify the business and expand margins. Within three years, Burger King had refranchised all but 52 of its company-owned stores, transforming itself into an almost entirely asset-light royalty collector.

Second, the valuation at entry made the opportunity even more compelling. At the time of the deal in 2010, Burger King was trading at roughly 8.5× forward EBITDA—definitely a notable discount to peers like McDonald’s (11–12×), Yum! Brands (12–13×), and Domino’s (14×+). Public equity investors had written the company off after years of weak comp sales, lackluster marketing, and inconsistent leadership. Yet 3G understood that if they could expand margins and rerate the multiple, the upside in equity value would be substantial. By the time Burger King re-entered the public markets via reverse merger in 2012, its valuation had climbed toward 14× EBITDA, driven by both operational improvements and changing investor perception.

Third, operationally, Burger King was bloated and bureaucratic. Its Miami headquarters employed over 800 people, and decision-making had become slow and diffuse. 3G moved quickly to impose zero-based budgeting, requiring all expenses to be justified from scratch. Corporate headcount was reduced by more than 60% within the first year. First-class flights, corporate jets, and other legacy perks were eliminated. Department budgets were scrutinized, reporting lines were flattened, and compensation became tightly linked to performance. The company’s general and administrative expenses as a percentage of revenue dropped sharply, driving operating leverage even before topline growth resumed. These early moves improved EBITDA by over 30% in less than three years and created the cash flow needed to deleverage the balance sheet.

Fourthly, the potential for international expansion added another critical layer to the thesis. Although Burger King had a large footprint, its brand penetration outside the U.S. was uneven. The company had previously exited key markets such as France, and it had minimal presence in the fastest-growing regions of the world—including Brazil, China, and India. 3G introduced a hub-and-spoke master franchise model to accelerate global expansion without deploying corporate capital. They signed deals with regional partners who brought local expertise and were responsible for development costs. This structure enabled Burger King to re-enter dormant markets and rapidly scale in emerging economies. Between 2010 and 2023, the global store count rose from 12,174 to over 19,000, and international franchisees became the primary engine of systemwide sales growth.

The fifth reason I chose here is about franchisee alignment, which has long been a source of tension, and 3G saw the potential to capitalize on it. Under previous ownership, Burger King had imposed pricing mandates that damaged operator economics—such as $1 menu promotions pushed through to drive comp sales regardless of unit-level profitability. 3G reversed that approach. The new leadership team worked to rebuild trust with franchisees by shifting toward collaborative planning and localized decision-making. As system-level EBITDA grew and franchisee margins recovered, operator reinvestment increased. This cultural shift, while less visible than the refranchising or budgeting changes, was essential in restoring health across the system.

Sixth, apart from business fundamentals, the timing of the deal also worked in 3G’s favor. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, interest rates were near record lows. The Burger King buyout was financed with approximately 70% debt, and the company’s stable royalty cash flows made it a natural candidate for securitized financing. Just two years after going private, Burger King re-entered the public markets through a merger with Justice Holdings, a UK-based investment vehicle. The reverse IPO not only provided liquidity but helped push enterprise valuation to over $8 billion, delivering an internal rate of return (IRR) in excess of 100% for 3G on its equity investment. As margins expanded and leverage declined, the public markets began to reward the company with a higher multiple—precisely the bet 3G had made from the start.

Seventh, and perhaps most interestingly 3G had a vision where Burger King could serve as a launchpad. 3G did not view the deal as a standalone asset to be flipped. Instead, it was the foundation of a longer-term platform strategy. In 2014, the firm executed an $11 billion merger with Tim Hortons to create Restaurant Brands International and designed the corporation to scale across global QSR brands. Over the following decade, RBI would acquire Popeyes, Firehouse Subs, and most recently announced a $9.4 billion deal to take Skechers private. Each of these businesses—diverse as they may seem—fit the Burger King mold: under-optimized brands with scale potential, strong cash conversion, and franchising leverage.

Thus, it is evident that 3G’s acquisition of Burger King was never about reinventing the burger business or a belief that they could make Burger King the number one burger chain in the world; it was more about retrieving and unlocking the long-trapped value of Burger King through disciplined execution. The business had structural advantages: high-margin royalties, a globally recognized brand, and enormous white space for expansion. But it was weighed down by bureaucracy, inconsistent leadership, and anemic capital allocation. Through refranchising, cost discipline, international scaling, franchisee realignment, and favorable capital markets timing, 3G reshaped Burger King into a cash-yielding, asset-light platform. What others saw as a tired fast-food chain, 3G saw as a mispriced compounder. And over the next several years, they proved it by making Burger King one of their most profitable deals yet.

Deal Structure

On October 19, 2010, 3G Capital completed its acquisition of Burger King Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: BKC*) in a transaction valued at approximately $4.0 billion, including the assumption of debt. The deal offered shareholders $24.00 per share in cash, a 46% premium to the stock’s closing price of $16.45 on August 31—the day before The Wall Street Journal reported the company was exploring a sale. The transaction provided a swift and sizable return for shareholders. Upon closing, Burger King became a private company, wholly owned by Blue Acquisition Holding Corporation, a 3G-controlled acquisition vehicle.

The deal followed a two-step merger structure, commonly used in public-to-private transactions. In the first step, 3G launched a tender offer through Blue Acquisition Sub, Inc., a special-purpose entity created for the deal. In a tender offer, the acquirer proposes to buy shares directly from shareholders—typically at a premium—allowing them to cash out without waiting for a formal vote. This method is faster than a traditional shareholder meeting and is especially effective in acquisitions where timing is critical.

Simultaneously, 3G initiated what’s known as a dual-track closing strategy—filing proxy materials with the SEC to prepare for a formal shareholder vote in case the tender offer failed to reach the necessary threshold. This backup plan ensured the deal could proceed via a longer but guaranteed route if required.

By October 15, over 93% of shares had been tendered, exceeding the 90% threshold under Delaware law to trigger a short-form merger—a legal mechanism that allows the acquirer to purchase the remaining shares without holding a vote. The second step was completed four days later. All remaining untendered shares were automatically converted into the right to receive the same $24.00 per share in cash. The combination of the two-step merger structure and the dual-track strategy—providing both speed and legal certainty—became known in dealmaking circles as the “Burger King structure.” It balanced fast execution with full control, minimized financing risk, and has since become a model for similar high-stakes take-private transactions.

On the financial side of things, of the roughly $4.0 billion deal value, approximately $2.8 billion was funded with debt, arranged by J.P. Morgan, Barclays, and other lenders. The remaining $1.2 billion in equity came from 3G Capital’s limited partners and principals. Though the leverage ratio was significant, 3G adopted a disciplined post-close approach. Unlike many private equity sponsors, they avoided early value extraction through dividend recapitalizations or sale-leasebacks. Instead, 3G focused on operational turnaround, refranchising, and free cash flow generation to reduce leverage over time.

Bernado Hees (Middle) and Daniel Schwartz (Right).

Leadership changes were also immediate. Bernardo Hees, a 3G operating executive with turnaround experience, was appointed CEO. Alexandre Behring, 3G’s co-founder and Managing Partner, became Co-Chairman of the Board alongside outgoing CEO John Chidsey, who remained temporarily to facilitate the transition. This marked the beginning of 3G’s owner-operator model at Burger King—an approach defined by zero-based budgeting, lean corporate teams, and rigorous performance accountability.

By 2012, Burger King returned to public markets through a reverse merger with Justice Holdings, a London-listed investment vehicle. In a reverse merger, a private company becomes publicly traded by merging with an existing public shell company, rather than going through a traditional IPO. This approach is often faster, requires less regulatory burden, and allows the acquirer to maintain greater control during the transition. For 3G, it offered a way to regain liquidity while preserving strategic leadership.

Given how things have played out in the years that followed, the structure of the Burger King deal—both legal and financial—was inseparable from the operational success that followed. The dual-track closing strategy minimized execution risk and secured full control early; the leveraged capital structure incentivized financial and operational discipline; the decision to avoid financial engineering in favor of long-term reinvestment positioned Burger King for its next phase of growth. It was because of this firm and intentional foundation that 3G had injected into the business that ultimately enabled the 2014 merger with Tim Hortons, forming the RBI that we know today.

Deal Discussion

1. Why Private Equity Loves Franchises

To understand why private equity shops continue to pursue franchised consumer businesses with such fervor, I feel like we must start with the simple arithmetic of franchising and what financial sponsors look for in businesses. Apart from the business fundamentals of achieving an economic moat from acquiring the brand equity and loyal customer base that often comes with a restaurant franchise, from a more purely financial perspective, two important things that PE investors look for in potential businesses to invest are steady, predictable cash flows and low CapEx. Simply put, if an investment generates predictable returns, PE investors can achieve better risk-adjusted returns because they would have a better idea of how much leverage would lead to optimal returns while mitigating default risk. As for CapEx, if the business is capital intensive, the financial sponsor will have to spend more cash to maintain business operations, thus having less free cash flow available to service debt and decreasing returns. So, ceteris paribus, investors prefer asset-light businesses.

Befittingly, franchisors, unlike traditional operators who must grapple with day-to-day restaurant-level execution, collect royalties off the top-line sales of independently owned stores—royalties that are insulated from rising labor costs, real estate volatility, and input price shocks. These contractual royalty streams are recurring, predictable, and scale beautifully with new store openings, making them eerily similar to the kind of annuity-like cash flows investors crave. A mature QSR brand might collect 4% to 8% in royalties on every dollar of gross sales while bearing little of the operational risk. It is, structurally, one of the cleanest ways to generate high EBITDA margins.

Similarly desired by investors is the low CapEx nature of the franchise model that allows for rapid expansion without the capital intensity typically associated with brick-and-mortar businesses. The key is that it is the franchisees, not the franchisor, who take on the risk and cost of building and operating new stores. If I wanted to open up a Burger King store today, I would not only have to pay an upfront franchise fee to the franchisor (the BK corporation) but also put up all the initial cash investment needed to build out the new store. For the franchisor, this capital-light growth engine enables the business to scale domestically and internationally at a pace most traditional companies can only dream of, while also retaining as much cash flow as possible to pay down debt.

Finally, add to this the rising prevalence of whole-business securitizations (WBS), which allow franchisors to borrow cheaply against their royalty streams by packaging those revenues into bond-like instruments, and the PE calculus becomes even more clear: healthy recurring cash flows, asset-light growth, and the cheap financing from financial engineering is the cherry on top of the icing. And recent deals have only reinforced the model's attractiveness. Blackstone's acquisition of Jersey Mike’s for roughly $8 billion and Roark Capital's purchase of Subway for $9.6 billion both reflect massive valuations that investors were still willing to pay due to strong unit economics and brand potential. In these transactions, financing packages often involved billions in WBS debt, allowing sponsors to take on more leverage to amplify returns while maintaining a manageable interest expense.

2. Why Burger King Succeeded Under 3G Capital: The Slash, Merge, Slash Again Playbook

Nevertheless, just because franchises have the foundation to become a desirable investment, there is still a lot of work left for the management in order for the business to succeed.

By 2009, Burger King was a 55-year-old chain in decline – losing traffic even as McDonald's grew during the recession. Shareholders were frustrated with weak sales and volatile costs squeezing earnings. In September 2010, 3G Capital announced a $3.3 billion buyout of Burger King ($4.0B including debt) at $24 per share. At the time, the chain was widely seen as a "fast food flameout", and analysts mocked the price as high for a struggling brand. Burger King's stock had fallen over 30% since 2008, underperforming McDonald's, and Wendy's was on the verge of overtaking it as the #2 U.S. burger chain (Wendy's $8.5B vs. BK's $8.4B in 2011 system sales). Clearly, 3G was inheriting a turnaround project.

3G's Turnaround Strategy: Under 3G's new, young leadership team, the playbook was immediate and aggressive. First, the team cut costs, stripping out corporate luxuries like private jets, lavish events, and redundant personnel. General & administrative expense was also cut to the bone, with overhead costs per restaurant reduced by nearly two-thirds. Even the workforce at BK's Miami corporate headquarters was also slashed by hundreds of jobs. Then, 3G started imposing a zero-based budgeting ethos – every expense had to be justified from zero each year. As a result, even small costs were targeted (e.g. employees' mobile phones were reclaimed unless essential, office supplies tightly rationed). This intense cost compression quickly shrank BK's SG&A burden and boosted margins.

Concurrently, Burger King undertook rapid refranchising to optimize for the desired asset-light business model. Within a couple of years, the company sold off almost all its company-operated restaurants to franchisees – all but 52 stores were franchised by 2013. These refranchising deals were tied to requirements that buyers invest in remodeling stores, ensuring the brand image improved without BK's capital. The refranchising strategy successfully transformed Burger King into the desired low CapEx franchisor model, dramatically reducing the capital intensity and direct operating costs. Though initially, reported revenues fell by more than half as company store sales came off BK's books, the higher-margin royalty and fee stream drove up profitability. Burger King also began repositioning its marketing and menu: management narrowed the menu to focus on core items, used data to hone offerings, and re-emphasized aggressive advertising. Franchisees initially wary of 3G's youth quickly grew "happy" as they saw better sales and profits under the new regime. So, despite revenue shrinking by about 50% due to refranchising, Burger King's net income nearly tripled within two years of 3G's takeover. By 2013, BK's Adjusted EBITDA margin was 58.1%, up from 33% in 2012, and 17-19% from the pre-3G era, reflecting the benefits of the lean cost structure and steady royalty income. Meanwhile, system-wide sales (including franchisee sales) were growing in the low-to-mid single digits as new franchised stores opened abroad and same-store sales stabilized. Burger King added a net of 670 restaurants in 2013 alone, particularly accelerating in Europe, Latin America, and Asia where master franchisees drove expansion.

In just a few years 3G’s strategic pivot created enormous value for owners. In June 2012, 3G relisted Burger King via a public offering at a $4.6B valuation. Just two years later (July 2014), Burger King's market cap had roughly doubled to $9 billion. Then, going into the next merger to form RBI in 2014, Burger King's market capitalization was nearly $12 billion – triple what 3G had paid in 2010. 3G had initially invested about $1.2–$1.5 billion of its own equity in the deal, and by 2016 the asset was estimated to be worth $12.5 billion. One analysis noted 3G paid back the initial capital within two years, and by 2016 had an asset eight times the purchase price. Pershing Square's Bill Ackman, a major co-investor, nearly quadrupled his money, and Warren Buffett (who bought preferred shares during a later deal) was also "minting $270MM in annual dividends" from Burger King's parent company. In total, it was reported that 3G and its fellow investors made over $14 billion from the Burger King turnaround in just seven years – a staggering payoff.

Having slashed costs to the bone in Burger King, we can see that 3G next moved to the "merge" phase of its playbook. In August 2014, Burger King announced a merger with Canadian coffee chain Tim Hortons (a $11.4B acquisition) to form a new parent company, Restaurant Brands International. The deal – backed by a $3B preferred investment from Buffett – was structured as a tax-efficient inversion, relocating the headquarters to Canada. 3G installed Burger King's CEO Daniel Schwartz (then 34) as CEO of RBI, and Burger King's global expansion chiefs took over Tim Hortons operations.

This platform strategy aimed to repeat the Burger King formula on a larger scale. Tim Hortons, while extremely profitable in Canada, had almost no presence internationally. 3G saw an opportunity to plug Tim's into Burger King's international franchise network, leveraging RBI's global scale. "Give us some time… you'll see more Tim Hortons in the U.S." Schwartz promised, emphasizing plans to accelerate Tim's growth globally. At the same time, there was clear intent to apply 3G's efficiency regimen to Tim Hortons' corporate structure. Even before closing, Canadian observers were anxious about possible cutbacks. A think tank warned that up to 700 jobs could be cut at Tim Hortons' headquarters post-merger. (3G had agreed with regulators to maintain "significant" employment levels in Canada for a period, somewhat limiting layoffs.)

But unsurprisingly under RBI, the slashing cycle continued: costs were "ruthlessly" cut at Tim Hortons to boost profits, and the remaining company-owned stores were refranchised as a result of Tim's selling all but 52 of its stores to franchisees. The immediate financial impact mirrored Burger King's story: Burger King's own net income had nearly tripled from 2011 to 2013 even as revenues halved, and now Tim Hortons' higher-cost structure would be slimmed down similarly. By combining the two brands, RBI also unlocked new scale economies in procurement, shared services, and international development. In 2017, RBI added Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen to its portfolio for $1.8B, executing another “roll-up” of a franchised fast-food brand and immediately applying the same formula where Popeyes' corporate G&A was reportedly cut by ~40% after 3G took over. Now we can see a pattern forming: each time 3G has cut all the fat they can in one company, they would "merge" with or acquire a company, then "slash again" – eliminating more overlapping costs, refranchising stores, and squeezing out efficiency gains to drive up margins. From 2010 through 2019, Restaurant Brands (including its Burger King predecessor) reportedly delivered an IRR well above 20% for 3G and its partners, validating the multi-stage "platform" approach. And by 2025, after tacking on Firehouse Subs and running what is likely the same playbook in 2021, RBI is now worth over $50 billion in enterprise value 15 years after what started as just the $1 billion worth of equity that 3G put up to acquire Burger King.

Yet, this aggressive Slash (and Optimize), Merge, Slash Again strategy wasn’t anything new to 3G. They’ve done it in several other cases too.

I thought it’d be cool to include this here. Source: Reddit

The 3G Formula in Brewing: AB InBev's Mega-Merger Machine

Even before Burger King, 3G’s Brazilian financiers Jorge Paulo Lemann, Marcel Telles, and Beto Sicupira had honed the slash and optimize, merge, slash again model in the beer industry. Starting in the 1980s, they built Brazil's Brahma brewery into a powerhouse, merged it with rival Antarctica to form AmBev, and then in 2004 merged AmBev with Belgium's Interbrew to create InBev. In 2008, InBev (with Lemann and partners as major shareholders) launched a $52 billion takeover of America's Anheuser-Busch – an unprecedented bold move that stunned the beer world. The combined Anheuser-Busch InBev, or AB InBev for short, became the largest brewer on the planet, and 3G installed its protégé Carlos Brito as CEO. Brito then executed the classic 3G playbook at Anheuser-Busch: layers of management were stripped out, budgets were zero-based (down to eliminating office perks like free beer, pens, and even an elevator being shut off to save power), and non-core assets (theme parks, packaging plants) were sold. Costs fell dramatically – one contemporaneous analysis noted InBev's plan would cut 10–15% of costs in year one, and another 5–10% in year two at Anheuser-Busch. In practice, AB InBev consistently achieved EBITDA margins above 40%, far higher than its more marketing-heavy rivals.

With costs slashed and AB InBev throwing off huge cash flows, 3G repeated the cycle: they pursued new mergers to drive growth. AB InBev acquired Mexico's Grupo Modelo in 2012 for $40B, then eyed an even larger target. In 2015, Brito set his sights on the No.2 global brewer SABMiller, and despite cultural differences— SAB's management was known for being brand-focused and decentralized, vs. AB InBev's "financial engineer" culture— the deal was struck in 2016 for a massive $109B. This was the capstone mega-merger, making AB InBev, an already leading player, into by far the dominant player with about 30% of the global beer market share. True to form, Brito's team immediately set about extracting "synergies" and cutting costs at the combined company. The SABMiller integration plan targeted $2+ billion in savings, and overlap was eliminated – including selling off several renowned beer brands like Miller, Pilsner Urquell, and Peroni to satisfy antitrust regulators and pay down some debt. By this time, AB InBev's reputation in the industry was cemented: it was a gigantic acquisition vehicle run by financial engineers who were relentless in cost-cutting and restructuring.

Though the reputation of the strategy has become somewhat notorious, for many years, AB InBev's strategy delivered superb financial results. The serial mergers helped AB InBev grow EBITDA fivefold from 2004 to 2016, and the company's market value swelled (post-SAB deal in 2016, AB InBev was valued at around $200B, up from $30B pre-InBev). The 3G team's focus on efficiency gave AB InBev the highest profit margins in brewing, enabling it to outbid competitors for acquisitions. However, by the late 2010s, signs emerged that this "slash-and-merge" cycle was reaching its limits. The debt load from the SABMiller purchase topped $100 billion, stretching the balance sheet. In 2018, AB InBev was forced to cut its dividend in half to conserve cash for debt service. At the same time, organic sales growth stalled – AB InBev's volumes were slipping as millions of consumers switched to craft beers and new alternatives, a trend Brito was slow to react to. Some investors began to question "whether a management team obsessed with cost-cutting is equipped to focus on organic growth" in this new era. After peaking around 2016, AB InBev's share price tumbled by over 50% (from $128 to the $50s by 2020), reflecting these concerns. In 2020, Brito – by then one of the longest-serving CEOs in the industry – announced his retirement amid calls for a strategic shift. As one beer trade publication noted, "Brito's strengths – no-nonsense deal-making and cost-cutting – have run their course", and the company signaled a pivot to a more growth-oriented leader.

Still, the AB InBev saga shows how closely it paralleled the Burger King pattern. At AB InBev, 3G executed repeated mergers followed by aggressive cost cuts, achieving enormous scale. The difference was that AB InBev eventually faced a saturated market and changing consumer tastes, exposing the limits of cost efficiency without innovation. Culturally, the 3G influence was profound: Brito inculcated the same frugal ethos company-wide. AB InBev's offices famously discouraged travel expenses and even minor perks ("Why not take the stairs?" signs urged employees after elevators were shut off to save money, which sounds pretty crazy right?). Performance was rewarded, but the environment was austere. Former employees describe AB InBev as a place of constant "nickel-and-diming" on costs, which intensified around 2015 as growth slowed. By 2021, AB InBev brought in a new CEO (Michel Doukeris) with a sales and marketing background, implying a shift in focus from M&A and efficiency toward brand-building and innovation. This marked a departure from the classic 3G formula, acknowledging that the "slash, merge, slash again" playbook alone may no longer be sufficient in the evolving beer industry.

The 3G Formula in Packaged Foods: Kraft Heinz's Big Bet and Backfire

If Burger King was 3G's shining success and AB InBev a massive, if debt-burdened, empire, Kraft Heinz represents the most troubled replication of 3G's approach. In 2013, 3G partnered with Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway to acquire H.J. Heinz Co. for $23 billion. Heinz, a classic consumer packaged goods company, offered the allure of "strong, non-cyclical brands" and heavy costs that 3G believed could be stripped out. As expected, 3G installed its team in Pittsburgh and immediately applied Zero-Based Budgeting across Heinz. The mandate: find $1.5 billion in cost savings at Heinz, which meant deep cuts to headcount and expenses. By 2014, Heinz's new Brazilian managers had eliminated thousands of jobs, closed factories, and dramatically reduced overhead. Heinz's operating margins jumped, and 3G had another success on its hands in terms of profitability improvement.

As we can guess now, the next phase was the “merge” step: In 2015, 3G teamed up with Buffet again and orchestrated a merger of Heinz with Kraft Foods Group, an even larger publicly traded CPG company, to form The Kraft Heinz Company. They paid about $40B for Kraft, a hefty premium that was even deemed as "overpaying" according to some critics but could be potentially justified by the enormous synergy potential and Kraft's bureaucratic culture was also ripe for 3G's cost-cutting scalpel. Upon the merger, hundreds of Kraft and Heinz veteran employees were RIF'ed (reduction in force), plants were shuttered, and cherished perks and traditions were eliminated. A once-stable, collegial culture quickly turned, in the words of a food industry columnist, into one of "dislike and distrust" within the organization.

Source: WSJ

For a brief period, the numbers looked good: Kraft Heinz's post-merger EBITDA margin soared as cost savings flowed straight to the bottom line, and by 2017 the company's stock hit an all-time high. 3G's reputation as cost-cutting kings appeared intact, and they even attempted a mind-blowing $143B takeover of Unilever in early 2017. However, that bid was abandoned within days after Unilever and UK regulators balked, amid "concerns about widespread cost-cutting" that 3G would bring.

After this failed merger, by 2018, Kraft Heinz's growth began to falter badly. Years of "over-indexing on cost cuts," as analysts would say, came home to roost. The company had severely under-invested in brand marketing, product innovation, and even maintenance of its supply chain. Multiple sources began criticizing 3G's approach: Retail grocery customers, AKA the supermarkets, were "pissed off" as Kraft Heinz cut trade promotions and raised prices to hit cost targets. Iconic brands like Oscar Mayer, Kool-Aid, and Kraft Mac & Cheese stagnated as 3G's budgets left little room for new product development or aggressive advertising. Internally, employees described morale as abysmal – "gutting the company" is how some put it, citing constant layoffs, scant resources, and a culture of fear that choked creativity.

By early 2019, the situation went from bad to worse: Kraft Heinz announced a stunning $15.4 billion write-down of its Kraft and Oscar Mayer trademarks, essentially admitting that years of cost-cutting had eroded brand equity to the point that these brands were worth far less than before. The same day, Kraft Heinz disclosed an SEC investigation into its accounting (mainly related to supplier rebates and cost recognition) cut its dividend by 36%, and posted weak sales – an "avalanche of bad news" that sent the stock plummeting. From its peak in 2017 to mid-2019, Kraft Heinz lost over 60% of its market capitalization, making it a poster child for the limits of the 3G playbook.

Industry observers did not mince words. A Food Industry news column declared Kraft Heinz "the poster boy of how not to purchase and reorganize a company", calling 3G's ZBB system "ridiculous… at least when applied to the CPG industry". The "zealousness and resulting toxicity" of 3G's cost cuts were blamed for alienating not only employees but also retail partners and consumers. Unlike restaurants or breweries, the CPG business relies on continuous marketing support and retailer relationships; as the column noted, in grocery, "relationships and trust still have some traction," and 3G's hardline budgeting left too little flexibility to keep retailers happy. In essence, 3G tried to run Kraft Heinz by the numbers alone, and it backfired when the landscape shifted and they remembered that there was an actual business to run. Even Jorge Paulo Lemann himself acknowledged in 2018 that the consumer brands area was changing in ways 3G hadn't anticipated: "I'm a terrified dinosaur," Lemann quipped, noting that new trends and disruptive startups had caught them by surprise. This was a remarkable admission from 3G's leader – that the old playbook was not infallible.

By 2019, 3G began to adjust course at Kraft Heinz. Long-time CEO Bernardo Hees, a 3G partner who had come from Burger King, was replaced by Miguel Patricio, a veteran marketing executive from AB InBev, tasked with rebuilding brand investment and repairing relationships. 3G also quietly started trimming its stake in KHC. The Kraft Heinz fiasco highlighted that while aggressive cost management and consolidation can create short-term value, over-reliance on cost-cutting carries significant long-term risks – especially in businesses where innovation and brand strength are critical.

The brands under Heinz and Kraft, respectively, before the Merger.

Comparing the Playbook: Similarities and Deviations

Strategic Parallels: Across Burger King, AB InBev, and Kraft Heinz, 3G Capital's overarching strategy showed clear patterns: an initial "slash and optimize" to cut costs and boost margins, a "roll-up/merge" to gain scale (often using the improved earnings as a springboard for acquisitions), followed by another round of "slash again" to squeeze out synergies and redundant costs in the merged entity. In all cases, 3G targeted mature companies with famous brands and what they viewed as excess costs or underutilized assets. The financial engineering – whether via leverage or tax-efficient mergers – was paired with an operational engineering of the business model: refranchising in restaurants, zero-based budgeting in consumer goods, and rigorous supply chain and overhead rationalization in brewing.

Burger King and AB InBev demonstrated that this formula, when executed well, can yield extraordinary investor returns and create highly efficient, cash-generative companies. For instance, AB InBev under 3G became a profit machine, at one point earning nearly $1 in every $3 of revenue as EBITDA, far above industry peers – a direct result of relentless cost discipline and global scale. Burger King's transformation into RBI similarly unlocked higher profit margins (RBI routinely posts ~30% operating margins, whereas pre-3G Burger King's operating margin was in single digits). In both companies, lean centralized management was a hallmark – by 2016 Burger King's entire corporate staff was only ~200 people overseeing a global empire, and AB InBev's headquarters headcount was famously small relative to its size. Another parallel was the incentive culture 3G instilled: top managers often have significant equity or bonuses tied to aggressive targets. At Burger King, 3G gave managers and even many employees stock options, aligning them with owners whereby in 2019, employees owned more of RBI than any shareholder except 3G itself. AB InBev likewise fostered an "owner-operator" mentality among its international cadre of MBAs. This cultural aspect – often dubbed the "3G way" – emphasizes meritocracy, youth, hunger, and cost consciousness, which contributed to the fast execution of changes.

Deviations and Lessons: Where the stories diverge is in the market context and limits of the model. Burger King operated in fast food – a sector where an "asset-light" franchisor model can thrive, and where cutting corporate fat doesn't directly degrade the product delivered by franchisees (provided franchisees reinvest some savings into their stores). Indeed, Burger King's brand has arguably held up; while it trails McDonald's, it remains a strong #2 or #3 player globally, and in recent years BK has even grown by clever marketing (often with limited spending). The brewery business also proved amenable to cost-led consolidation for a long time – beer consumption is relatively steady, and marketing synergies (e.g., combining global brands under one portfolio) gave AB InBev extra leverage. However, AB InBev taught 3G that even a dominant player can falter if it misses shifts in consumer preference (craft beer, health trends) – a reminder that efficiency cannot replace innovation.

Kraft Heinz was the clearest caution. In food retail, brand equity, and innovation are the lifeblood, and 3G's model left KHC unable to respond when niche brands and private labels nibbled away at its big brands' relevance. 3G treated Kraft Heinz's brands as if they would thrive simply by cutting the "fat," but failed to nurture some of America's most well-known products that needed reinvestment. The consequence was a rapid deterioration in brand health – something that doesn't show up quarter-to-quarter until it's too late (hence the huge goodwill write-down in 2019). Additionally, the organizational impact at Kraft Heinz was overwhelmingly negative: the company reportedly suffered high turnover and difficulty attracting new talent, as its reputation became that of a cost-cutters enclave rather than an innovator. This contrasts with Burger King, where many younger executives thrived under 3G's meritocratic, high-paced environment (a number of 3G's BK alumni have gone on to lead other companies). It suggests that the 3G culture can be energizing in some contexts and demoralizing in others – likely depending on whether employees see growth opportunity or just endless cuts.

Finally, the role of debt and financial leverage differed. At Burger King and Kraft Heinz, 3G used significant leverage in the buyouts, enhancing equity IRRs but also necessitating strong cash flows. They managed to pay down Burger King's debt quickly (helped by refranchising proceeds), whereas Kraft Heinz's debt became an albatross when earnings underperformed – by 2020 KHC had to refinance, and asset sales were considered to reduce debt. AB InBev, meanwhile, took on massive debt for SABMiller and struggled under it when beer sales softened. Thus, the limits of high leverage emerged as a lesson: the "merge" phase can overreach, leaving a company more vulnerable if the anticipated growth or synergies don't fully materialize.

In summary, the ‘Slash → Merge → Slash Again’ strategy engineered by 3G Capital has proven to be a powerful value-creation engine – turning an underperforming Burger King into a thriving global platform and building AB InBev into a colossus. It has validated that radical cost efficiency when combined with savvy deal-making and global expansion, can unlock tremendous shareholder value in mature businesses. At the same time, its replication in different contexts has illuminated the strategy’s boundaries and pitfalls. The Burger King story worked because cost cuts were paired with re-energizing the franchise network and brand. In less forgiving areas like consumer-packaged goods, the same zeal to cut became self-defeating, prompting calls for a more balanced approach. As of 2025, 3G appears to be evolving – hiring leaders with more focus on brand-building (e.g. Miguel Patricio at Kraft Heinz, Patrick Doyle at RBI) and allowing higher expense budgets where needed. The legacy of 3G’s experiment is a nuanced one. It has shown that shareholder capitalism can be jolted forward by eliminating waste and scaling up – but also that sustainable success requires investing in the product, the brand, and the people, not merely compressing costs. In evaluating 3G’s impact, one executive’s comment perhaps sums it up best: “Doing the business basics…can have enormous returns”, and ignoring longer-term fundamentals can just as easily come back to bite. The 3G playbook applied thoughtfully, remains a formidable strategy – yet its most important lesson may be that great companies cannot be run on cost-cutting alone.

3. When Other PE-Franchise Deals Failed Outside of 3G

Red Lobster: Financial Engineering Disconnected from Operational Reality

Red Lobster presents a recent example of private equity failure— one driven by aggressive financial engineering that is fundamentally misaligned with the operational needs of the business. When Golden Gate Capital acquired Red Lobster from Darden Restaurants for $2.1 billion in 2014, the private equity firm promised to revitalize the aging seafood chain and position it for standalone success.

Instead of investing in brand rejuvenation, however, Golden Gate immediately executed a complex financial maneuver: a $1.5 billion sale-leaseback transaction on Red Lobster's extensive real estate portfolio. In this arrangement, the company sold its real estate assets to investors, then immediately leased those same properties back—effectively converting ownership into rental payments. For Golden Gate, this maneuver was brilliant financial engineering, allowing them to recoup approximately 70% of their initial investment just months after the acquisition. But for Red Lobster as an operating business, this transaction fundamentally transformed its cost structure, creating a heavy burden of lease expenses that would eventually prove unsustainable.

The sale-leaseback converted what had been a significant asset base into a substantial liability. The company went from owning most of its locations to paying substantial rent with 2% annual increases across its entire restaurant footprint. By 2023, these lease obligations had ballooned to approximately $190 million annually—with many leases priced significantly above prevailing market rates. This dramatic shift left "little room for error" in a casual dining segment already challenged by changing consumer preferences and rising competition.

The substantial fixed costs from the leases created severe operational constraints. Red Lobster needed to maintain unusually high profit margins just to cover its lease obligations, putting pressure on food quality and portion sizes. With so much cash flow directed toward rent payments, the chain had minimal resources available for menu innovation, restaurant renovations, or marketing to revitalize the aging brand. Unlike a company that owns its real estate, Red Lobster couldn't easily close underperforming locations without continuing to pay rent or negotiating costly lease buyouts. These constraints severely limited management's ability to adapt to changing market conditions.

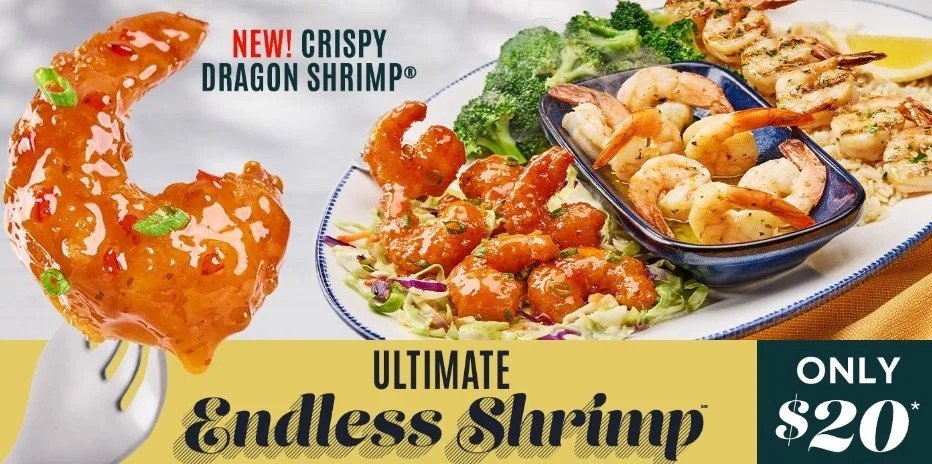

The breaking point, as suggested by many in the media, was Red Lobster’s ill-fated "Endless Shrimp" promotion in 2023. Designed to drive traffic during a period of declining sales, the unlimited offering succeeded in attracting customers but at a devastating cost. Food expenses soared as guests consumed far more of the high-cost protein than the company had projected. With its already-thin margins squeezed by lease obligations, Red Lobster had no financial cushion to absorb these operational miscalculations. By early 2024, the chain was hemorrhaging cash at an unsustainable rate, and in March 2024, Red Lobster filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. In court filings, the company specifically cited the "above-market leases" as a primary cause of its financial distress.

Red Lobster's downfall vividly illustrates the dangers of financial engineering disconnected from operational reality. The sale-leaseback transaction delivered immediate returns to Golden Gate Capital but created an inflexible cost structure that the business simply couldn't support over the long term—especially when faced with changing consumer preferences, rising food costs, and operational missteps.

Quiznos: A Perfect Storm of Over-Leverage and Franchisee Exploitation

If Red Lobster represents a recent cautionary tale, Quiznos stands as the classic historical case study of how a promising restaurant chain can implode under private equity ownership. Acquired by CCMP Capital in 2006 for approximately $850 million, the sandwich chain was immediately burdened with hundreds of millions in debt—a classic leveraged buyout where the acquisition is largely funded with borrowed money, leaving the acquired company responsible for repaying it.

What made the Quiznos situation particularly toxic was how this financial burden intersected with an already problematic franchise model. The company employed what industry observers called a "churn and burn" strategy: recruiting new franchisees aggressively while imposing economically unsustainable conditions on existing operators. Franchisees faced a double squeeze through mandatory purchasing requirements that forced them to buy virtually all supplies—from meats and cheeses to paper products—exclusively from Quiznos-approved vendors at prices significantly above wholesale market rates. These vendors then paid rebates to Quiznos corporate, essentially creating a hidden profit center at franchisees' expense. Simultaneously, as Quiznos raced to expand, the company frequently opened new locations in close proximity to existing franchisees, sometimes just blocks away. This territorial cannibalization maximized franchise fees and supply markups for corporate but devastated individual store economics.

The franchise model's fatal flaws became increasingly apparent as franchisees began struggling financially. A wave of lawsuits followed, with operators alleging predatory practices and misrepresentation of potential profits. Several franchisee class-action suits filed between 2006 and 2009 created substantial legal liabilities for the company. Meanwhile, the leveraged business model assumed continued rapid growth—an expansion that would generate enough cash flow to service the mounting debt. But instead of growing, Quiznos began to shrink dramatically as franchisee revolts intensified and store closures accelerated. The company's location count plunged from approximately 4,700 stores in 2007 to fewer than 1,500 by 2013.

By the time Quiznos filed for bankruptcy in 2014, the once-promising chain was burdened with approximately $875 million in debt with little ability to pay it. The bankruptcy saw equity owners completely wiped out, with creditors taking ownership of what remained—a shell of what had once been the second-largest sandwich chain in America. The Quiznos collapse reveals a fundamental truth about franchise-focused private equity deals: even the most financially engineered transaction cannot succeed when the underlying unit economics for franchisees are unsustainable. The formula proved devastatingly simple: excess debt combined with franchisee exploitation created system-wide collapse.

4. So, is Private Equity a Blessing or a Curse for the Business World?

By now, one truth should be clear: private equity is neither savior nor saboteur by nature. It is a force—powerful, precise, and often unforgiving. It can transform a sluggish, bloated enterprise into a high-margin, globally scaled machine. It can also, just as quickly, hollow out a brand, suffocating its potential under debt, rent, and neglected innovation. But at the very core of private equity, I think can be seen as a powerful lever whose ultimate impact rests entirely in the hands of those who wield it.

The case of Burger King under 3G Capital offers the most instructive version of the former. With sharp discipline, a well-sequenced strategy, and a measured pivot toward reinvestment, 3G engineered one of the most successful consumer buyouts in modern private equity history. Through zero-based budgeting, aggressive refranchising, and a deliberate scale-up of international royalty streams, 3G slashed Burger King’s costs, stabilized its operations, and positioned it for growth—all while delivering significant returns to shareholders.

Contrast this with the disasters at Red Lobster and Quiznos, where private equity was used not to strengthen brands but to drain them. Financial engineering like Red Lobster’s sale-leaseback and Quiznos' excessive leverage offered tempting immediate rewards, but at the cost of long-term viability. When short-term cash extraction becomes the core objective, it inevitably destroys brand value, alienates franchisees, and strips businesses of their ability to adapt, innovate, and thrive.

At Kraft Heinz, we saw the limits of relentless austerity. Cost discipline, so valuable initially, quickly turned into a toxic obsession. Without a subsequent pivot toward reinvestment, even iconic brands began to wither, demonstrating painfully that efficiency alone is never enough. Brands, like flames, require oxygen to burn—storytelling, innovation, and authentic customer connection.

I think the takeaways and lessons for investors and business owners are clear:

1. Financial engineering must serve strategy: Leverage, dividend recaps, sale-leasebacks, etc., enhance returns only if aligned strategically.

A key to private equity’s success—or its failure—is the alignment of incentives among investors, management, and operational units (like franchisees). Under 3G, Burger King initially faced profound misalignment, with unhappy franchisees and bloated corporate structures. Yet 3G effectively reset these incentives. By refranchising aggressively, Burger King pushed operational accountability to franchisees, aligning their profitability directly with the brand’s health. At the corporate level, zero-based budgeting (ZBB) and drastic overhead reductions refocused management incentives toward efficiency and sustainable growth, transforming previously skeptical franchisees into committed growth partners.

In stark contrast, Red Lobster and Quiznos show what happens when incentives are misaligned. Golden Gate Capital prioritized short-term financial extraction through aggressive sale-leasebacks, burdening Red Lobster with inflated, inflexible lease obligations. Franchisees and management faced impossible cost pressures without sufficient strategic support. Similarly, Quiznos, under CCMP Capital, destroyed franchisee profitability and trust through costly vendor agreements and unsustainable store expansions. Without aligned incentives, even the most clever financial maneuvers devolve into damaging short-termism.

2. Operational discipline requires reinvestment: Cost discipline creates necessary breathing room but must always be balanced with strategic reinvestment in brand, product, and people.

Operational discipline, exemplified by Burger King’s zero-based budgeting, drives meaningful short-term efficiency. Yet Burger King thrived precisely because cost-cutting served as a platform—not a perpetual strategy. Cost discipline was quickly matched by substantial reinvestment in brand marketing, menu innovation, and international expansion. In contrast, AB InBev, another 3G-led company, eventually faltered when relentless cost-cutting hindered necessary innovation in a changing beer landscape. Kraft Heinz similarly underscored this limitation—operational austerity without strategic reinvestment inevitably weakens brand equity and competitive positioning.

Thus, private equity success hinges on recognizing this critical balance: efficiency must be paired with thoughtful reinvestment to sustain competitive advantage and adapt to shifting markets.

3. Financial engineering needs to serve a purpose that helps align investor and operator incentives toward the long-term, sustainable growth of a business.